Understanding Autism Spectrum: From Asperger’s and High-functioning Autism to Individualised, Tailored Sensory Rooms

Autism, or autism spectrum disorder (ASD), is a complex neurobiological developmental disorder that, according to the DSM-5 (2013), affects social interaction, communication, behavior, and sensory perception. Since it is a spectrum, symptoms, and challenges can vary significantly from person to person, each individual having a unique combination of characteristics and abilities.

Contents

What is autism (ASD)?

Autism, also known as autism spectrum disorder (ASD), is a neurodevelopmental condition characterized by difficulties in social interaction and verbal and nonverbal communication, as well as the presence of repetitive behaviors and restricted interests. It is typically recognized in early childhood, with diagnosis based on behavioral observations and professional assessments. Since autism affects various developmental areas, its manifestation varies among individuals and can change throughout a lifetime (National Framework for ASD Screening and Diagnosis, 2015).

The modern approach to autism emphasizes that it should not be viewed solely through a clinical lens but as part of natural human diversity. Autism is a neurological difference that influences how a person thinks, communicates, interacts, and perceives the world. There is no cure for autism, as it is not a disease with physical symptoms but rather a specific way in which the brain functions.

In recent decades, the prevalence of autism has significantly increased, partly due to improved diagnostic methods and greater awareness of the condition. According to the World Health Organization (WHO, 2021).

Diagnosis and Early Signs of Autism

Autism is typically diagnosed between the ages of two and four, although some symptoms can be recognized even earlier. Early signs of autism include:

Lack of interest in social interaction

Delayed speech development or absence of speech

Avoidance of eye contact

Repetitive behaviors

Unusual play patterns (e.g., lining up toys instead of engaging in symbolic play)

Causes and Risk Factors

The exact cause of autism is still not fully understood, but research indicates a complex combination of genetic and environmental factors that influence early brain development. Rather than a single specific cause, autism develops under the influence of multiple interconnected factors.

· Genetic Factors – Studies have identified a link between specific genes and autism, suggesting that genetic predisposition plays a key role in its development (Sandin et al., 2017).

· Prenatal and Perinatal Factors – Certain environmental influences, such as infections during pregnancy, premature birth, and low birth weight, may increase the risk of developing autism (Gardener et al., 2011).

· Neurobiological Factors – Research has shown differences in brain structure and function in individuals with autism, indicating specific neurological characteristics associated with this condition (Courchesne et al., 2019).

Key Characteristics of Autism

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is characterized by difficulties in three main areas: social interaction, communication, and repetitive behaviors with restricted interests.

Difficulties in social interaction manifest as challenges in understanding and using nonverbal communication, such as eye contact, facial expressions, and gestures. Individuals with autism may have a limited understanding of social rules, making it difficult for them to establish and maintain relationships, recognize and interpret the emotions of others, and participate in group activities (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Difficulties in communication range from a complete absence of speech to a well-developed vocabulary but with challenges in understanding language pragmatics. Some individuals with autism may experience delayed speech development, repeat words or phrases without understanding (echolalia), and speak in a monotone or unusual manner. They often interpret language literally, making it challenging to understand metaphors, jokes, and figurative expressions (Lord et al., 2020).

Repetitive behaviors and restricted interests include stereotypical actions such as rocking, tapping, or hand-flapping, as well as a firm adherence to routines and resistance to change. Individuals with autism may develop intense interests in specific topics, such as trains, astronomy, or numbers, to which they devote significant attention (Hyman et al., 2020).

These characteristics vary in intensity and expression, making each person with autism unique in how they perceive and interpret the world around them.

Depending on the child's age, the visible characteristics of autism may change. Below is a table outlining the key characteristics of autism based on age:

High-functioning autism spectrum disorder

High-functioning autism refers to individuals on the autism spectrum who have average or above-average cognitive abilities, yet still experience significant difficulties in social communication, behavioural flexibility, and sensory processing. Although it is not a formal diagnostic category in DSM-5, the term continues to be used in research and clinical practice to describe specific profiles within ASD (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Individuals often demonstrate stronger visuospatial and nonverbal abilities, while their verbal skills tend to be uneven, especially when early language delays are present (Lai et al., 2015). Studies also show greater cognitive and adaptive heterogeneity in comparison with individuals who were historically diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome, including weaker pragmatic communication skills and everyday functioning (Ghaziuddin & Mountain-Kimchi, 2004; de Giambattista et al., 2019).

Despite their intellectual strengths, challenges in social understanding, emotional regulation, and sensory reactivity continue to significantly affect quality of life, which is why individualised, functionally oriented support is recommended (King et al., 2014).

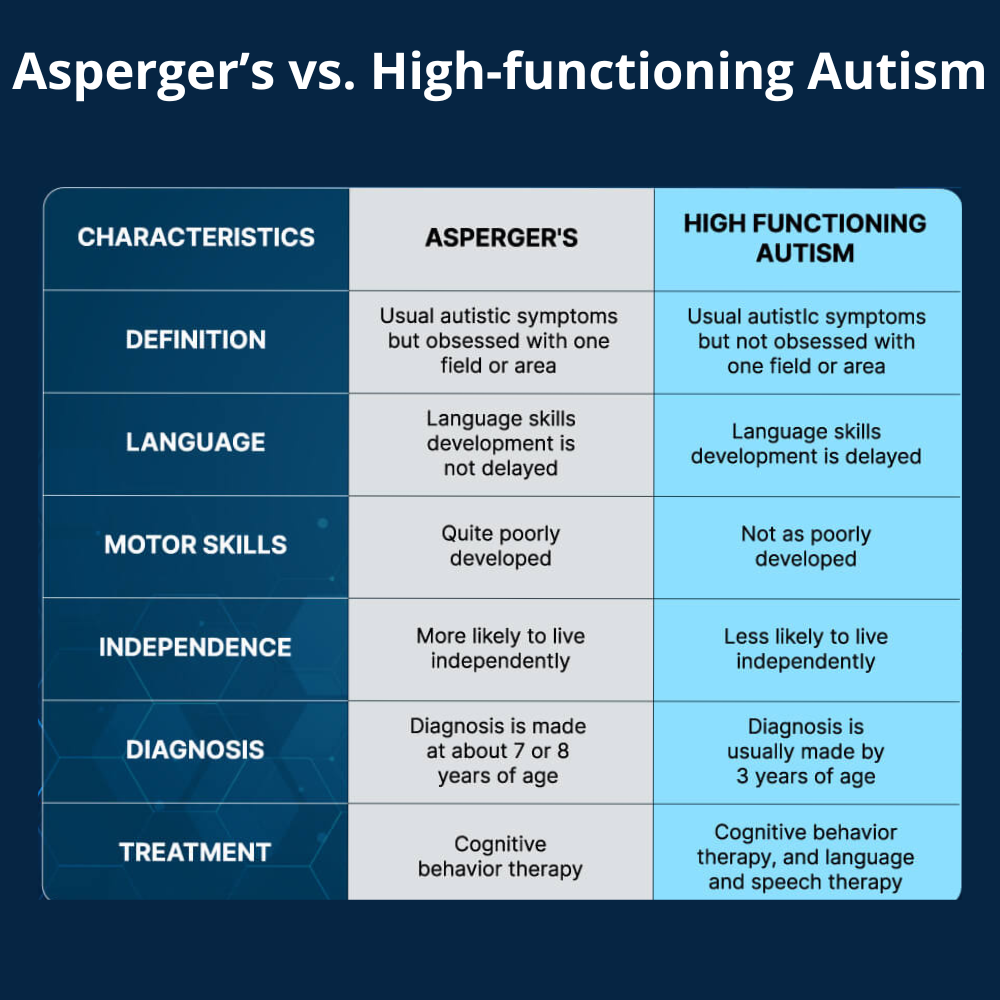

Asperger vs. Autism

Asperger’s syndrome and autism are now considered parts of the same neurological spectrum because they share core difficulties in social communication and exhibit repetitive patterns of behaviour (Wing, 1997). Historically, differences stemmed from the fact that individuals with Asperger’s syndrome, according to DSM-IV criteria, did not have delays in language or cognitive development, whereas other forms of autism more often involved intellectual and language impairments (Klin, 2003).

However, research shows that the differences between Asperger’s syndrome and high-functioning autism are primarily quantitative, with substantial overlap in their profiles (de Giambattista et al., 2018), which contributed to the removal of Asperger’s syndrome as a separate diagnosis in DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Although they are now unified under the single term ASD, some patterns still differ: individuals with Asperger's syndrome typically do not show language delays, often achieve higher scores on verbal cognitive measures, and function better in daily life, whereas the high-functioning autism group shows greater heterogeneity, more frequent early language delays, and stronger visuospatial abilities (APA, 2013; Lai et al., 2015, Boschi et al., 2016 Giambattista et al., 2019).

Due to such overlap and variability, contemporary clinical practice emphasises individualised assessment of strengths, challenges, and support needs, rather than strict differentiation between diagnostic subtypes (King et al., 2014).

Sensory Processing and Autism

Individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) often experience difficulties with sensory integration, meaning their brain processes and responds to sensory stimuli from the environment differently. These sensory challenges typically manifest in three primary forms:

Hyposensitivity – Reduced sensitivity to certain stimuli, which may lead to seeking intense sensory experiences such as spinning, rocking, or touching various textures. Some individuals with autism may have a reduced sense of pain or temperature.

Hypersensitivity – Increased sensitivity to light, sound, touch, smells, or tastes can cause discomfort, stress, or sensory overload in everyday situations. For example, bright lights or loud noises may be highly distressing and trigger anxiety.

Difficulties with sensory integration—Problems with processing multiple sensory inputs simultaneously can make activities such as dressing, eating certain foods, or participating in group environments challenging (Dunn, 2007; Baranek et al., 2013).

Sensory difficulties can significantly impact daily functioning and quality of life for individuals with autism. In this context, sensory integration therapy can help regulate sensory challenges and facilitate environmental adaptation (Schaaf & Benevides, 2018).

Given the common sensory integration challenges in individuals with autism spectrum disorder, it is crucial to ensure that different environments provide opportunities to meet their sensory needs in a socially acceptable manner. This is where SENcastle plays a vital role. SENcastle is a compact sensory room designed to function as a small-scale sensory space that can be integrated into educational and healthcare institutions and everyday living spaces, creating a sensory oasis where individuals can fulfill their sensory needs.

By using various sensory cards in combination with six different sensory cushions, individuals can customize sensory input according to their unique needs, whether they require more or less stimulation. Once their sensory needs are met, they can return to their planned daily activities with improved focus and engagement.

Sensory Rooms for Autism

Sensory rooms represent structured multisensory environments designed to support the regulation of arousal, attention, and emotional states in individuals on the autism spectrum by providing controlled visual, tactile, auditory, and proprioceptive stimuli. Research shows that such environments can reduce stress, improve self-regulation, and enhance engagement in learning and therapeutic activities (Sánchez et al., 2011; Stephenson & Carter, 2011).

Since children and adults with autism often experience atypical sensory processing, including hyper- or hyporeactivity to stimuli, multisensory environments help mitigate these challenges by creating a safe space where sensory information can be organised and behaviour regulated (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Schaaf et al., 2014).

People with Asperger's syndrome and high-functioning autism have similar sensory issues and can also benefit from the use of sensory rooms. Studies further indicate that using a sensory room prior to demanding tasks can improve focus and reduce disruptive behaviours, particularly among children with pronounced sensory difficulties (Anderson et al., 2017), making sensory rooms a valuable complementary approach that supports reduced anxiety, strengthened adaptive skills, and greater participation in educational and therapeutic contexts.

Given the frequent sensory integration challenges experienced by individuals with autism spectrum disorder, it is essential to provide environments that allow sensory needs to be met in a socially acceptable and functional way — and this is precisely where SENcastle plays a key role. As a compact, modular sensory room, SENcastle enables the creation of a multisensory space within educational, healthcare, and everyday environments, offering a "sensory oasis" where individuals can meet their sensory needs through the combination of different sensory cards and six types of sensory cushions. It represents a perfect sensory room equipment for autism.

SENcastle also allows the intensity of sensory input to be tailored to individual needs, whether a person requires more or less stimulation, ultimately enabling them to return to daily activities with improved focus, calmer behaviour, and greater engagement.

Therapies and Interventions

While there is no universal cure for autism, various therapies and approaches can significantly improve the quality of life for individuals with autism. Interventions focus on supporting the development of communication, social, and adaptive skills and adapting the environment to facilitate daily functioning.

The most commonly used interventions include:

Behavioral Therapies – Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) therapy has been proven effective in developing communication and social skills while reducing unwanted behavioral patterns.

Speech and Occupational Therapy – Speech therapy helps develop verbal and nonverbal communication, while occupational therapy supports sensory integration and essential daily skills needed for independence.

Educational Support – Tailored educational programs and individualized approaches are crucial for the successful learning and socialization of autistic children.

Pharmacological Interventions – Although they do not treat autism, certain medications can help manage symptoms such as anxiety, aggression, and hyperactivity, thereby improving overall quality of life.

Since autism encompasses a wide range of needs and abilities, the most effective approach involves individualized support tailored to each person's specific needs.

World Autism Awareness Day

World Autism Awareness Day is observed on April 2nd. Its goal is to raise awareness and provide support for individuals with autism and their families (United Nations, 2007). On this day, people wear blue as a symbol of support for individuals with autism.

Blue has been recognized as the color of autism because it symbolizes calmness, trust, and awareness. The organization Autism Speaks prominently uses blue in the global "Light It Up Blue" campaign.

References:

· American Psychiatric Association. (2013): Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). American Psychiatric Publishing.

· Anderson, C., Smith, V., & Taylor, J. (2017): Effects of multisensory environments on behavior and engagement in children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(6), 1680–1691.

· Baranek, G. T., Woynaroski, T., Nowell, S. W., Turner-Brown, L., DuBay, M., Crais, E. R., & Watson, L. R. (2013): "Sensory features as diagnostic criteria in autism: Challenges and opportunities." Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(5), 1177-1191.

· Boschi, A., Planche, P., Hemimou, C., Demily, C., & Vaivre-Douret, L. (2016): From high intellectual potential to Asperger syndrome: Evidence for differences and a fundamental overlap—A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1605.

· Courchesne, E., Pramparo, T., Gazestani, V. H., Lombardo, M. V., Pierce, K., & Lewis, N. E. (2019): "The ASD cortical signature: Distinctive neuroanatomical features of autism spectrum disorder." Annual Review of Neuroscience, 42, 285-307.

· de Giambattista, C., Ventura, P., Trerotoli, P., Margari, M., Palumbi, R., & Margari, L. (2018): Subtyping the autism spectrum disorder: Comparison of children with high functioning autism and Asperger syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(1), 96–109.

· Dunn, W. (2007): Supporting children with autism spectrum disorder through sensory-based interventions. OT Practice, 12(17), 1-7.

· Gardener, H., Spiegelman, D., & Buka, S. L. (2011): Perinatal and Neonatal Risk Factors for Autism: A Comprehensive Meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 128(2), 344-355.

· Ghaziuddin, M., & Mountain-Kimchi, K. (2004): Defining the intellectual profile of Asperger syndrome: Comparison with high-functioning autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 34(3), 279–284.

· Hyman, S. L., Levy, S. E., & Myers, S. M. (2020): "Identification, evaluation, and management of children with autism spectrum disorder." Pediatrics, 145(1), e20193447.

· Lai, M.-C., Lombardo, M. V., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2015): Autism. The Lancet, 383(9920), 896–910.

· Lord, C., Elsabbagh, M., Baird, G., & Veenstra-VanderWeele, J. (2020): "Autism spectrum disorder." The Lancet, 392(10146), 508-520.

· King, B. H., Navot, N., Bernier, R., & Webb, S. J. (2014): Update on diagnostic classification in autism. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 27(2), 105–109.

· Klin, A. (2003): Asperger syndrome: An update. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 25(2), 103–109.

· Ministarstvo zdravlja Republike Hrvatske. (2015): Nacionalni okvir za probir i dijagnostiku poremećaja iz spektra autizma.

· Sánchez, A., Millán, J., & Martínez, D. (2011): Multisensory rooms and their impact on children with autism. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 58(2), 175–189.

· Sandin, S., Lichtenstein, P., Kuja-Halkola, R., Hultman, C., Larsson, H., & Reichenberg, A. (2017): The Heritability of Autism Spectrum Disorder. JAMA, 318(12), 1182-1184.

· Schaaf, R. C., Benevides, T., Mailloux, Z., Faller, P., Hunt, J., Hooydonk, E., et al. (2014): An intervention for sensory difficulties in children with autism: A randomized trial. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(7), 1493–1506.

· Schaaf, R. C., & Benevides, T. W. (2018): Autism and the sensory integration approach. American Occupational Therapy Association.

· Stephenson, J., & Carter, M. (2011): The use of multisensory environments in schools for students with autism: A review of the literature. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41(5), 685–701.

· United Nations. (2007). "World Autism Awareness Day." UN General Assembly Resolution 62/139.

· Wing, L. (1997): The autistic spectrum. The Lancet, 350(9093), 1761–1766.

· World Health Organization (2021): Autism spectrum disorders fact sheet.